India is poised to reach its full potential and regain its rightful place at the top of the world order

Given the deep pools of capital required and the new technologies to be adopted as the consensus builds to achieve climate justice, India will surely be an important recipient of both.

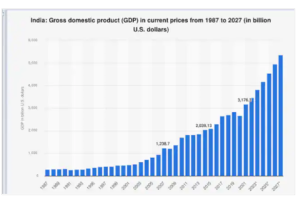

It took India 60 years (from 1947 to 2007) to reach its first trillion dollars of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Graph 1 shows that the next trillion took 8 years (2007 to 2015), and India was at the edge of touching the $3 trillion mark on the eve of Covid.

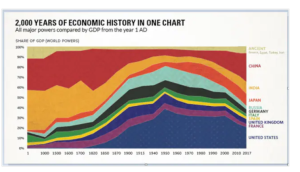

As our leaders and experts have repeatedly told us, we should add $1 trillion every 3 to 4 years. Graph 2 shows that for most of history (from 1 AD to 1820), India and China dominated the world economy, so reverting to mean requires us to play with a straight bat and not throw away our wicket and advantage.

In 2022, our macros compare favourably to the United States (US), China, Germany and the United Kingdom (UK). We are growing at double the pace of any other large economy, and after a very long time, we have lower inflation than the US, UK and Germany. Add to this the geopolitics, Ukraine war and climate transition, and the poly crisis jumps out at you (“economic and non-economic shocks are entangled all the way down”, Adam Tooze). However, as Mr Jayant Sinha has said of climate change, we need to turn the vast and urgent challenge into a huge opportunity for jobs, innovation and growth in India, given our abundance of access to clean energy sources, in particular, solar and wind. Given the deep pools of capital required and the new technologies to be adopted as the consensus builds to achieve climate justice, India will surely be an important recipient of both.

Similarly, our leadership of the G20 comes at a pivotal moment, and China plus one strategy and our entry into the “Quad” puts India in a critical position. We will have stiff competition, especially from our ASEAN neighbours, who may have a head start in skilling their labour force. Still, none of them has the scale of the domestic market and labour pool we are blessed with (e.g. Vietnam, which has done well to date, is running at virtually full capacity). Therefore, we must play to our many strengths and continue working on our bottlenecks, such as infrastructure, labour productivity and social security. This is not the time for a shotgun approach but focused and execution/target-based initiatives.

India has done a splendid job in building world-class digital public goods. They are such an inspiration for other countries that Margrethe Vestager, the European Commissioner for Competition, recently said, “the Indian stack shows that if we want people to embrace technologies, we need trust and inclusiveness…..EU must emulate this”.

If we can add over 240 million bank accounts in just two years (2015-16) and issue 300 million sophisticated identity cards (Aadhaar) in just one year (2013-14), why can’t we get our physical infrastructure to match if not, exceed the very basic global standards. This has to include hard and soft infrastructure, especially education and healthcare, once again making full use of our technological/digital prowess. We cannot sustain a 7-8 per cent GDP growth without a matching infrastructure growth.

The major issues and their solutions are well-known and have been widely discussed, debated and written about for at least two decades. Just two examples are the power discoms issue and the deepening of our bond and private credit market. This has gained importance given that we need $30-40 billion of private credit even at our current GDP. This is in spite of the fact that our credit/GDP ratio is a conservative 56 per cent (primarily supplied by our banks). With the benefit of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (one of the two game-changing legislations, with GST being the other) passed by the parliament in recent years, this should be imminently doable.

Most likely, the new year will be like an opening batter facing a new swinging ball on a wet wicket in England under overcast skies and with poor visibility. This is not a year for a Sehwag innings. It requires an innings that is cautious but with one being ready to take advantage of loose balls, capitalising on our world-class skills and macroeconomic strengths. As the year passes, the sun will undoubtedly shine through (cycles by name must turn), the ball will wear out, and the outfield will dry up. At that point, we can revert to hitting boundaries and growing at 8 per cent. The bottom line is that we should aim for an innings with the magic and artistry of G Viswanath or Kohli, but should keep in mind that the grit and determination of a Gavaskar or Dravid innings will also ensure we fulfil our potential and regain our rightful place at the top of the world order.

It took India 60 years (from 1947 to 2007) to reach its first trillion dollars of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Graph 1 shows that the next trillion took 8 years (2007 to 2015), and India was at the edge of touching the $3 trillion mark on the eve of Covid.

As our leaders and experts have repeatedly told us, we should add $1 trillion every 3 to 4 years. Graph 2 shows that for most of history (from 1 AD to 1820), India and China dominated the world economy, so reverting to mean requires us to play with a straight bat and not throw away our wicket and advantage.

In 2022, our macros compare favourably to the United States (US), China, Germany and the United Kingdom (UK). We are growing at double the pace of any other large economy, and after a very long time, we have lower inflation than the US, UK and Germany. Add to this the geopolitics, Ukraine war and climate transition, and the poly crisis jumps out at you (“economic and non-economic shocks are entangled all the way down”, Adam Tooze). However, as Mr Jayant Sinha has said of climate change, we need to turn the vast and urgent challenge into a huge opportunity for jobs, innovation and growth in India, given our abundance of access to clean energy sources, in particular, solar and wind. Given the deep pools of capital required and the new technologies to be adopted as the consensus builds to achieve climate justice, India will surely be an important recipient of both.

Similarly, our leadership of the G20 comes at a pivotal moment, and China plus one strategy and our entry into the “Quad” puts India in a critical position. We will have stiff competition, especially from our ASEAN neighbours, who may have a head start in skilling their labour force. Still, none of them has the scale of the domestic market and labour pool we are blessed with (e.g. Vietnam, which has done well to date, is running at virtually full capacity). Therefore, we must play to our many strengths and continue working on our bottlenecks, such as infrastructure, labour productivity and social security. This is not the time for a shotgun approach but focused and execution/target-based initiatives.

India has done a splendid job in building world-class digital public goods. They are such an inspiration for other countries that Margrethe Vestager, the European Commissioner for Competition, recently said, “the Indian stack shows that if we want people to embrace technologies, we need trust and inclusiveness…..EU must emulate this”.

If we can add over 240 million bank accounts in just two years (2015-16) and issue 300 million sophisticated identity cards (Aadhaar) in just one year (2013-14), why can’t we get our physical infrastructure to match if not, exceed the very basic global standards. This has to include hard and soft infrastructure, especially education and healthcare, once again making full use of our technological/digital prowess. We cannot sustain a 7-8 per cent GDP growth without a matching infrastructure growth.

The major issues and their solutions are well-known and have been widely discussed, debated and written about for at least two decades. Just two examples are the power discoms issue and the deepening of our bond and private credit market. This has gained importance given that we need $30-40 billion of private credit even at our current GDP. This is in spite of the fact that our credit/GDP ratio is a conservative 56 per cent (primarily supplied by our banks). With the benefit of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (one of the two game-changing legislations, with GST being the other) passed by the parliament in recent years, this should be imminently doable.

Most likely, the new year will be like an opening batter facing a new swinging ball on a wet wicket in England under overcast skies and with poor visibility. This is not a year for a Sehwag innings. It requires an innings that is cautious but with one being ready to take advantage of loose balls, capitalising on our world-class skills and macroeconomic strengths. As the year passes, the sun will undoubtedly shine through (cycles by name must turn), the ball will wear out, and the outfield will dry up. At that point, we can revert to hitting boundaries and growing at 8 per cent. The bottom line is that we should aim for an innings with the magic and artistry of G Viswanath or Kohli, but should keep in mind that the grit and determination of a Gavaskar or Dravid innings will also ensure we fulfil our potential and regain our rightful place at the top of the world order.

Graph 1

Graph 2