Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and Its Impact in India

Introduction

On December 11, 2019, the European Commission unveiled its ambitious climate change strategy, the “European Green Deal” which aims to achieve carbon neutrality within the European Union (“EU”) by 2050. This program seeks to significantly reduce the EU’s greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions. As part of the Green Deal’s core policy package, the European Commission introduced a legislative proposal on July 14, 2021, establishing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (“CBAM”). The CBAM primarily functions as a measure designed to ensure imported products bear a carbon emission cost comparable to that imposed on goods produced domestically within the EU[1].

The year 2024 has witnessed heightened scrutiny in India regarding the potential ramifications of the CBAM on Indian exports destined for the EU market. For India, the implications of the CBAM extend beyond mere reductions in exports to the EU and their associated economic consequences. The mechanism raises concerns about its compatibility with principles of equity, efficiency, and established international frameworks like the Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (“CBDRRC”) principle and agreements under the World Trade Organization (“WTO”).

What is the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism?

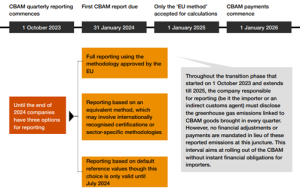

The CBAM is a policy instrument implemented by the EU designed to address the issue of carbon leakage. Carbon leakage occurs when industries relocate production facilities to jurisdictions with less stringent carbon pricing regulations, effectively circumventing the provisions under the EU’s Emission Trading Scheme (“EU ETS”). The CBAM aims to ensure a level playing field by imposing a carbon price on imports of certain high-carbon-intensity goods. These goods are deemed to be at a higher risk of contributing to carbon leakage[2]. The CBAM was introduced in a phased approach. A transitional period commenced on January 1, 2023, with formal publication to occur on January 1, 2026. During the initial period, a reporting system was established for specific goods starting in 2023. EU importers will rely on emissions data provided by exporters, who must submit documentation on their processes every two months. The CBAM will be enforced in the same manner as the EU customs legislation[3]. To offer legal clarity and stability to enterprises and other nations, the CBAM will be brought in gradually and will initially apply exclusively to a limited range of goods considered susceptible to carbon leakage viz., cement, electricity, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizer and chemicals[4].

Commencing in 2026, importers must make financial adjustments based on the carbon emissions embedded in imported goods. They must disclose the quantity and emissions of these goods by May 31st each year and purchase certificates to match the emissions. The revenue from the CBAM will go to the EU’s general budget. As CBAM is implemented, free allowances under the EU ETS will be phased out to ensure fair competition between domestic and imported goods and among imports from different countries[5].

Impact of CBAM on Indian Market

The implementation of the CBAM presents significant administrative and technical challenges for Indian producers. The reporting obligation, effective from October 2023, mandates the disclosure of the quantity of imported goods, their embedded carbon emissions, and any applicable carbon costs incurred in the exporting country. This requirement poses significant challenge for Indian exporters, who in the absence of proper technological means must adhere to the EU standards by monitoring, calculating, reporting, and verifying emissions. Small Indian industries may face disadvantages similar to those experienced during the implementation of EU’s Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (“REACH”) Regulation in 2006[6]. The CBAM framework has also established a mechanism for determining the carbon footprint of imported goods in instances where precise embedded emissions data is unavailable. In such scenarios, default values will be utilized. These default values are derived from the best available secondary data on the carbon footprint of CBAM-covered goods. However, if reliable data remains inaccessible, the default values will be based on the average emissions intensity of the worst-performing installations within the relevant EU Emissions Trading Scheme (“EU ETS”) sector[7]. Furthermore, total declared emissions must undergo verification by accredited verifiers. India’s inadequate data infrastructure for emissions collection may necessitate default emission data usage, potentially resulting in increased costs due to mark-ups imposed by the European Council.

CBAM Reporting Timelines[8]

The second phase of the CBAM will place a financial burden on EU importers. Starting in 2026, importers must purchase CBAM certificates for the emissions embedded in goods imported into the EU, effectively acting as a tax at the border. This could lead to higher prices for CBAM-covered goods in the European market, potentially affecting India’s exports in specific sectors and their competitiveness, depending on production emission intensity and reliance on the EU market. Indian exporters should evaluate the financial impact of the CBAM certificate requirement, especially if EU importers pass these costs onto them. This is particularly relevant considering the possibility of EU importers seeking to pass on the costs of these certificates to Indian exporters[9]. In such scenarios, Indian exporters should prioritize constructive negotiations with their EU counterparts to minimize the impact of CBAM certificate costs on their operations.

India is expected to be significantly affected by the CBAM in its exports of aluminum and iron and steel, as the EU is a major market for these commodities. Around 27% ($2.7 billion) of India’s aluminum and 38% ($3.7 billion) of its steel exports go to the EU[10]. Annually, India exports about USD 8 billion worth of CBAM-covered goods to the EU, with 26.6% of its iron ore pellets, iron, steel, and aluminum products destined for this market[11]. The impact of the CBAM’s “tax” on Indian exports will arguably be higher due to its reliance on coal-fired electricity. While India is adding renewable energy capacity of 203.1 GW and expects to add about 500 GW by 2030, transitioning completely to renewable energy remains a challenge due to factors such as investment in infrastructure, integrating renewable energy into the existing power grid, and managing the intermittent nature of sources like solar and wind.

What Lies Ahead for India?

India’s current carbon pricing regime, with a tax rate of USD 1.6 per tonne of CO2 emissions, is among the lowest globally[12]. The transition to carbon free energy and methodologies of production are cost extensive, for industries indvividually and for the Indian economy as a whole. Indian exporters confront the prospect of increased production costs, reduced demand within the European market, and heightened competition from EU producers. The Indian government has vehemently contested the CBAM, characterizing it as a discriminatory measure that constitutes a substantial trade barrier. This perspective extends beyond India, with other developing nations echoing similar concerns. The CBAM is specifically criticized for functioning as a non-tariff barrier that undermines existing zero-duty free trade agreements (“FTA”). The perceived contradiction lies in India incurring a levy while simultaneously facilitating duty-free entry for supposedly ‘green’ products from the EU. The WTO has also raised concerns regarding the fairness of the EU’s policy, particularly considering India’s commitment to the Paris Agreement and its established goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2070[13]. The imposition of a carbon tax on imports contradicts the EU’s and developed nations’ commitments to supporting the green transition of other countries, potentially leading to a flow of funds in the opposite direction.

India has strongly opposed the CBAM at the WTO and is taking proactive measures domestically to protect its interests and promote sustainable development. These measures include aiming to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030 and introducing a Carbon Credit Trading System (“CCTS”).[14] Given India’s existing burden of substantial energy taxes, exploring the conversion of these levies into carbon price equivalents for export calculations within CBAM-impacted sectors presents a potential avenue for mitigating the economic repercussions of increased trade costs. Furthermore, India could pursue negotiations with the EU and the UK for the establishment of Free Trade Agreements (“FTA”). Discussions with the EU should prioritize the allocation of CBAM revenues towards supporting green transitions in developing countries. This approach aligns with the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” enshrined within the Paris Agreement. In bilateral negotiations, India could also explore the possibility of including clauses that provide for a deferral of the CBAM and its application. As an additional strategy to protect Indian interests, India is contemplating the implementation of its own carbon tax on exports to the EU, with the proceeds potentially used to fund domestic clean energy initiatives[15]. As also suggested by Global Trade Research Initiative (“GTRI”), India could use a twin strategy of a calibrated retaliation mechanism to retaliate in equal measure and rename some ongoing schemes as carbon taxes to deal with the EU’s climate taxes. This could serve as an interim measure until India’s CCTS is fully operational. These proactive measures can help India navigate the challenges posed by CBAM while protecting vulnerable economic sectors in the short term.

Conclusion

The CBAM presents a potential catalyst for the international community’s transition towards low-carbon pathways. However, its unilateral implementation by the EU raises concerns regarding the lack of meaningful consultation with trading partners and key international stakeholders. The EU’s actions arguably reflect an inward-looking policy agenda that contradicts the principles of globalization previously championed by Western nations on the international stage. The success of the CBAM hinges on fostering international cooperation. This necessitates the establishment of consensus on methodologies for carbon footprint calculation and the implementation of robust data-sharing mechanisms.

The EU’s unilateral implementation of the CBAM carries the risk of exacerbating existing power imbalances. Industrialized nations, having historically consumed a significant portion of the global carbon budget with minimal repercussions, now exert undue influence over developing economies[16]. India’s concerns highlight potential impacts on its industries, especially in carbon-intensive sectors such as aluminum and steel. Addressing these challenges effectively necessitates a multifaceted approach: engaging in free trade negotiations, establishing a domestic Carbon Credit Trading Scheme, advocating for equitable distribution of CBAM revenues, and exploring options for imposing a carbon tax on EU exports. By pursuing these measures, India can actively contribute to achieving global sustainability objectives while simultaneously safeguarding its legitimate economic interests within the framework of international trade law.

Footnotes:

[1]“Press Corner” (European Commission – European Commission)<https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_3661> accessed July 4, 2023.

[2] Carbon leakage refers to the relocation of production to other countries with laxer emissions constraints for costs reasons related to climate policies, which could lead to an increase in their total emissions. See <https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/allowances/leakage_en> accessed on 4 July 2024.

[3] (2022) ‘Impact of EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism’ KPMG

[4] Kardish, C. (2022) ‘Carbon Border Adjustments: Considerations for Policymakers’, Centre for Climate and Energy Solutions.

[5] ibid

[6] Gupta, A. and Pandey, R. (2024) ‘Potential implications of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism’, NIPFP Working Paper Series.

[7] ibid

[8] ‘FAQs on the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism’ (2024) Price Waterhouse and Coopers (pwc).

[9] ibid

[10] Priya, P. (2024) ‘Decoding CBAM: How will EU’s carbon levy impact India’.

[11] ibid

[12] Saptakee S (2024) ‘India Challenges EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)’.

[13] Gupta, supra note 5

[14] Miller, D. (2024) ‘Can we make the CBAM work for India?’ Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

[15] Priya, supra note 8

[16] Miller, supra note 12